APH: Blindness Field Legend Took Part in Selma Marches

By Micheal Hudson, Director, Museum of the American Printing House for the Blind

This article was originally posted on Fred’s Head from APH, a Blindness Blog.

Although our museum and archives collections center on the history of education and rehabilitation for people who are blind and visually impaired, they also document the impact of outside forces on those very subjects. As our nation prepares to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Selma to Montgomery, Alabama marches, it seems appropriate to share this unique connection between the blindness field and the national Civil Rights Movement.

American Printing House for the Blind entered into a partnership with the Carroll Center for the Blind to help preserve the papers of rehabilitation pioneer and Hall-of-Famer Father Thomas J. Carroll (1909-1971). There are countless fascinating documents that help us understand the roots of rehabilitation for blinded veterans, adults, and senior citizens. One in particular, however, helps us understand the depth of Carroll’s empathy and humanity.

Alabama State Troopers attack John Lewis at the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

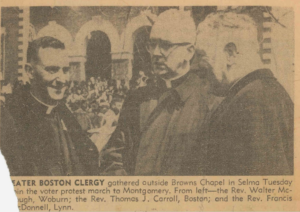

Tom Carroll was a Catholic priest, a priest who was vitally interested in the changes that were sweeping though post-war America. In early March of 1965, he watched on TV with the rest of America as unarmed demonstrators in Selma, Alabama were gassed and brutally beaten by white officers. When the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. made a national appeal to clergy of all denominations to join him in Selma for a second march on March 9th, Carroll answered the call.

The first march, on March 7, was organized locally, in response to the murder on February 18 of civil rights activist Jimmie Lee Jackson by an Alabama state trooper. Met by state troopers and gangs of loosely organized sheriff’s deputies as the marchers tried to cross the infamous Edmund Pettus Bridge, the demonstrators were turned away in a violent melee that became known as “Bloody Sunday.”

As Carroll lined up on the morning of March 9, prepared to put his own life on the line for social justice, events behind the scenes were unfolding to prevent a similar disaster, although only King and a few others knew it. Federal District Court Judge Frank Johnson had issued a restraining order prohibiting the second march. In Johnson, King felt he had a potential ally, and wanted to avoid angering the judge by violating the order. King and the demonstrators confronted the National Guard on the bridge, but retreated after prayer and singing in what became known as “Turnaround Tuesday.”

Newspaper clipping showing Father Carroll and two other clergy members gathered at Selma.

That night, one of the marchers, a minister from Boston named James Reeb, was killed in Selma by members of the Klu Klux Klan. Aware of the danger, Carroll had already left the state.

In the aftermath, Judge Johnson issued his famous ruling, “The law is clear that the right to petition one’s government for the redress of grievances may be exercised in large groups.” This led to the third march, from Selma to Montgomery, March 21-25, 1965.

Tucked into the Carroll Papers is a four page transcript of a teleconference between Carroll and prayer groups dated March 13th, 1965, where he describes his experiences on the second Selma march. Carroll’s prose is raw and immediate. It is obvious that his experiences in Selma have touched and changed him.

We found this video of “Turnaround Tuesday” in the National Archives. When the marchers kneel to pray, the tall, gray-haired gentleman in the dark coat and dark glasses who leans on his cane and remains standing is… Father Thomas J. Carroll. He had been hospitalized for more than a year in 1957-58, suffering from phlebitis in his legs, and was left physically unable to kneel.